In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

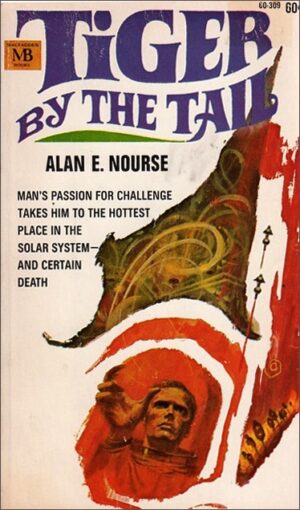

In the latter part of the 20th century, the science fiction community began to move past its lurid pulp origins and become part of respectable culture. The genre began to leave behind covers featuring bug-eyed monsters and scantily clad maidens and turned toward plots that depended thoughtful scientific extrapolation rather than simply generating thrills. Of course, as Alan E. Nourse shows in the collection Tiger by the Tail, those stories can still be fun and compelling.

I had read Tiger by the Tail in a library edition when I was young, having discovered the work of Alan E. Nourse because largely because of geography—his juvenile books were shelved right beside those of Andre Norton in the young adult science fiction section of the local library. The copy I used for this review came from my father’s extensive collection of science fiction books and magazines, long stored in our basement, which my brothers and I divided up after my father’s death in 2002. Opening it for the re-read and smelling the musty odor of the pages immediately brought back memories of the days when we all picked our favorites from the collection, which turned out to be a surprisingly easy task. While there was some overlap in our favorites, each of us had different books that we remembered fondly for different reasons. Now, picking up those volumes always triggers a wave of nostalgia for me. I know my father would be glad his books are being read and loved by the next generation of readers.

About the Author

Alan E. Nourse (1928-1992) was a physician who also had a long and productive writing career. He wrote science fiction, mainstream fiction, non-fiction books on science and medical issues, and penned a column on medical matters that appeared in Good Housekeeping magazine. I previously reviewed his juvenile novel Raiders from the Rings here, and there is a more complete biography contained in that review. Like many authors of his time, some of Nourse’s work is out of copyright, and available for reading on the internet for free (including a few stories from this collection—see here for work available on Project Gutenberg).

The Search for Respectability

As the 20th century progressed, the writers of the science fiction genre longed to throw off the reputation gained during the lurid pulp days, during which the genre had been branded as a less serious form of literature. One reason motivating this change was economics, as writing is a chancy business at best, and all writers want financial stability. The other reason was a longing to be taken seriously, to be respected for their craft and their accomplishments. Most observers point toward the late 1930s and 1940s as the start of an era of increased respectability for the genre, the period often called the Golden Age of Science Fiction. The effort was led by editors such as John W. Campbell at Astounding Science Fiction, who replaced the lurid pulp covers with more serious illustrations. He also favored stories that contained thoughtful speculation and scientific accuracy (for the most part, although he also sometimes flirted with pseudo-science such as telepathic powers, reactionless space drives and perpetual motion).

After World War II, science fiction novels began to be published by mainstream publishers, and new, more serious publications like The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction began to compete with Astounding. Robert Heinlein broke into the pages of The Saturday Evening Post in 1947, and went on to serve as the technical advisor for a new and better quality science fiction movie, Destination Moon. In 1950, in a break from his previous pulp output, Ray Bradbury wrote The Martian Chronicles, the first of his many books that would garner attention outside the science fiction community. Astounding changed its name to Analog, a less sensational title that fit the magazine’s new direction. Arthur C. Clarke’s 1961 novel A Fall of Moondust was the first science fiction novel chosen as a Reader’s Digest Condensed Book. And from 1963 to 1965, Analog expanded from the pulp digest format to that of mainstream “slick” magazines.

The copy of Tiger by the Tail I read for this review is a book club edition from 1961, from the Science Fiction Book Club (SFBC) which had been started by Doubleday in 1953. The cover sports a sedate illustration showing an impressionistic sun surrounded by planets in their orbit, which I am pretty sure is the same illustration used for the general edition of the book. The copy on the back cover makes it clear that the SFBC was also bidding for respectability, and wanted to expand their audience beyond the world of established science fiction fans:

TODAY’S FICTION—TOMORROW’S FACTS. LIFE Magazine says there are more than TWO MILLION science fiction fans in this country. From all corners of the nation comes the resounding proof that science fiction has established itself as an exciting and imaginative NEW FORM OF LITERATURE that is attracting literally tens of thousands of new readers every year! Why? Because no other form of fiction can provide you with such thrilling and unprecedented adventures! No other form of fiction can take you on an eerie trip to Mars…amaze you with a journey into the year 3000 AD…or sweep you into the fabulous realms of unexplored space! Yes, it’s no wonder that this exciting new form of imaginative literature has captivated the largest group of fascinated new readers in the United States today!

It is easy to see why the SFBC would use this approach to advertise a book by Alan E. Nourse, a writer whose work was clever and witty, but also rooted in solid scientific knowledge and speculation, especially in stories related to the medical field. He was the type of writer who personified a new, still exciting, but more serious approach to science fiction.

Tiger by the Tail

The book contains stories first published between 1951 and 1961, in several of the era’s leading and well-respected magazines.

The title story, “Tiger by the Tail,” appeared in Galaxy Magazine. Nourse was fond of interdimensional tales that pitted protagonists against the unknown, and this is a strong example. It starts with the arrest of a shoplifter filling her purse with an amazing amount of product. The purse is immediately taken to the nearby Institute of Physics for closer examination, because it is inexplicably empty. The physicists find an aluminum ring inside the purse, and the woman was stealing aluminum items. The shoplifter has no recollection of what she was doing and why. The scientists suspect the purse is a portal to another world. Perhaps the woman was under telepathic control…perhaps whoever is on the other side wants to build a bigger portal? Nourse is at his best explaining scientific possibilities in a clear, understandable way. The scientists put a hook through the portal, attempting to bring something from the other dimension back into ours—then the other side begins to pull back, and they begin to wonder if they’ve done the right thing.

“Nightmare Brother,” which was published in Astounding Science Fiction, is a story of a man locked into strange dreams. Slowly but surely, he learns to overcome the challenges he faces. Attempts to travel to other stars have all ended with the crews going insane, and this is a last-ditch attempt to figure out why, and overcome the problem. The story shows the influence of editor John Campbell, who was especially fond of stories involving psychological challenges and mental powers.

“PRoblem,” (the capitalized PR is intentional) is from Galaxy Magazine, and is another tale of international hijinks. Peter Greenwood is a public relations man—one of the best. Members of an alien race, the Grdznth, are appearing out of nowhere, using Earth as a way station in their efforts to flee a dying world. The aliens are polite and friendly, but tempers are flaring. The government needs to figure out a way to get humanity to sympathize with the Grdznth and accept their temporary presence. But just as Greenwood and his compatriots find a way to appeal to people’s compassion, the whole situation comes apart at the seams.

“The Coffin Cure,” another story from Galaxy, is a classic tale of unintended consequences. A team of doctors has developed a cure for the common cold. Their arrogant team leader steals credit for the discovery, and in his quest for glory, pushes deployment of the vaccine much more quickly than he should. But when the vaccinated begin to recover the sense of smell that has been being suppressed by cold viruses for uncounted generations, they begin to wonder if maybe colds were such a bad thing after all…

“Brightside Crossing” starts from the viewpoint of James Barron, who wants to travel across the bright side of Mercury (the story having been written in the days when Mercury was thought to be tidally locked, and always presenting the same face to the sun). He is insistent on doing what no other man has been able to do (in addition to a tidally locked Mercury, these were the days when the default for adventurers in stories was male). But then he is visited by Peter Claney, the sole survivor of the previous failed attempt at a brightside crossing, and hears the tale of heroism and hubris that led to its downfall. This tale, which totally misses the fact that orbiting ships and satellites could produce detailed maps of unexplored areas, also appeared in Galaxy.

“The Native Soil” is the sole story in the collection from the magazine Fantastic Universe. Under its clouds, Venus has proved to be a planet of mud, inhabited by creatures the visitors from Earth think are clumsy and unintelligent. But in that mud are deposits of a new antibiotic, desperately needed on an Earth where bacteria are increasingly resistant to such treatments (this is a constant concern for doctors, which continues to this very day). The collection efforts, however, depend on those native creatures, and are going awry. So, Piper Pharmaceuticals sends its best troubleshooter. (This was a common framework for stories in those days—in my youth, based on my science fiction reading, I assumed the world was filled with clever troubleshooters.) As is often the case, it turns out the actual situation, once revealed, bears no resemblance to everyone’s preconceived notions.

The always-quirky Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction was the original home for “Love Thy Vimp,” another tale of visitors from another dimension. The planet is being plagued by disgusting and irritating gibbon-like creatures that are dubbed Vimps, an acronym for Very Important Menacing Problems. As you might guess from the title, the secret to solving the problem doesn’t involve giving the hateful little creatures the reaction they are trying to evoke.

In “Letter of the Law,” a con man from Earth has traveled to a new world to fleece its occupants, and then calls on Earth’s diplomats to extract him from the alien prison he ends up in. But the Earth representative expects him to stand trial on a planet where lying is a way of life. It’s con man versus a corrupt court in a story full of delightful twists and turns, the last twist being one that is centuries old. This story came from IF Magazine.

The last tale, “Family Resemblance,” which appeared in Astounding, is set in a hospital, a setting familiar to Nourse. There is a pompous senior doctor whose favorite subject, and next book, is about how man is descended from the ape. But one of the younger doctors has an alternate theory, and Nourse pulls out all stops to convince the reader he has a valid point. In the end, the story wraps up in one of the most egregious puns I have ever encountered.

Final Thoughts

Alan E. Nourse was a favorite author of mine in my youth. Even now, every time I encounter another of his stories, I find the experience delightful. He is one of those science fiction authors, largely forgotten today, who deserve wider recognition—after all, it was people like Nourse who helped build a wider and more respectable reputation for the genre.

I would enjoy hearing from any of you who have also read Nourse’s work, as well as any suggestions you may have for other lesser-known writers who deserve to be better remembered and more widely read.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.